Services

- Home

- Mental Health

- Who We Treat

- How We Treat

- Patients & Visitors

- About

- Lexington

close

I do not remember ever having a desire to live. I kind of just float around and go through the motions of people telling me what to do and what they want from me.

Eventually, people stopped telling me what to do and asking me to do things, so now it is up to me to force myself out of bed, force myself to get ready for the day, force myself to eat, force myself to work, and then lay awake at night not wanting to do it again tomorrow.

Joy? I don’t remember how that feels.

For 30 years I have been looking for answers to life's struggles, and there has never been an answer. I know that mental illness runs in my genes, but I have never seen anyone do anything about it.

Everyone else just gets by, so I guess that is what I have to do, but I don’t want to just keep getting by.

An estimated 17.3 million American adults had at least one major depressive episode in 2017, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. That totals 7.1 percent of the population.

Kentucky is very much part of the trend of growing mental health disorders. According to a recent Kentucky Health Issues Poll, 50 percent of Kentuckians know someone in the state that is battling depression.

Nationally, 18 percent of adults are considered to have experienced depression at some point in their lives. That is roughly 59 million Americans.

In Kentucky, the rate is even higher. The Bluegrass State ranks third in the United States for incidences of depression at 23.5 percent. That is just over one million of our fellow Kentuckians facing depression.

The number is only going to continue to climb, as recent research shows. Between 2014-18, the rate of depressed individuals in Kentucky rose by .42 percent.

As with any state, there are pockets where certain traits are more prevalent than others. The rates of depression in Kentucky are higher than other states, with an added boost from certain regions in the state.

In the Appalachian area of the state, an area that has spent many years in economic depression, the state finds its citizens facing the most mentally unhealthy days per month. In Clay County, the average person has 10 mentally unhealthy days per month.

Martin County, Lee County, Menifee County, and Breathitt County all tie for the second highest rate of mentally unhealthy days per month at 9 days per person per month.

While this area of the state struggles, more research has shown that the Kentuckians in this area are also not seeking care. Research has indicated that only 50 percent of the female residents of Eastern Kentucky counties are receiving treatment for their depression.

Many factors lead to the cause of the lack of treatment received by these citizens, that we will touch on a little later in the article.

The women of Eastern Kentucky are not the only underserved population in the state in terms of mental health treatment.

The African American population also adds to the total of persons who are not receiving treatment that is needed. While the Black community is more likely to report mental and emotional distress, only 33% receive treatment.

While the African American population in Kentucky is just 8.3 percent, less than the national total, the number of Black Kentuckians not receiving treatment is well into the tens of thousands.

The eastern side of the state and the central and urban communities are not the only ones lacking treatment. Recent studies have shown that the westernmost counties in Kentucky have taken a sharp turn for the worse in mental health and substance use, as their suicide rates are now leading the state and are well above the national average.

Among the counties that have the highest increases in rate and highest total rate are Hickman, Ballard, and Carlisle.

The study from The Ohio State University shined light on one county in particular. Union County, which sits in the northwest corner of the state bordering Indiana and Illinois, met the national average for suicide from 2002-04. In the most recent time period, 2014-16, Union County had a suicide rate double the national rate.

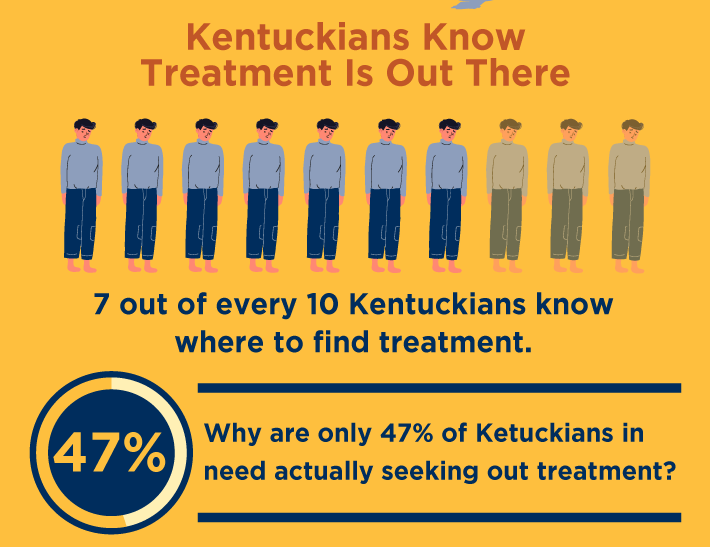

Despite the need for treatment by so many Kentuckians, there is survey proof that Kentuckians just completely ignore their needs for treatment. The Kentucky Health Issues Poll of 2016 found that seven out of every 10 Kentuckians know where to find treatment.

With 70 percent of the residents of The Bluegrass State knowing where treatment is available, why are only 47 percent of those in need actually going to, and receiving, the treatment needed?

SUN Behavioral Kentucky Health Director of Clinical Services, Sharon Simmons, LCSW, PhD., has noticed two prevailing reasons for this, especially in rural Eastern and Western Kentucky counties.

“First, stigma is still very much an issue and appears to be more prevalent in Southern states and rural areas,” Simmons said. “Second, the cultural differences in Western and Eastern Kentucky appear to have an impact on stigma in those areas as well. For example, I’ve worked in rural Western Kentucky and nearly all of my patients had the pervasive feeling that they should just be able to overcome it or snap out of it. They generally have a difficult time accepting that they might need medication or counseling services. It is very much a cultural belief in rural communities that it’s okay to have heart disease, but it’s not okay to have depression. These things all work together to deter treatment.”

Stigma is not cool. There is no better way to say it.

Assistant Dean for Clinical Nursing Education at LSU Health New Orleans, Benita Chatmon, summed up her experiences with a study in the American Journal of Men's Health. She summed up stigma into one definition:

“Mental health-related stigma is an umbrella term that includes social (public) stigma, self-stigma (perceived), professional stigma, and cultural stigma. Social stigma refers to the negative attitudes toward, and disapproval of, a person or group experiencing mental health illness rooted in misperception that symptoms of mental illness are based on a person having a weak character. These perceptions can lead to discrimination, avoidance, and rejection of persons experiencing mental illness.”

In essence, stigma is what people face that makes them feel less than, or separated from society as a whole, because of their perceived condition.

Because of stigma, many individuals will avoid treatment for their mental health disorders. Stigma has revealed its ugliness in studies into mental health showing that those that have received treatment have faced it at an alarming rate.

In the above study, nearly 15 percent of those that were in treatment for mental health disorders in the past 12 months perceived stigma in their lives. Most notably, the stigma came forth among those with lower educational attainment, those married, and those that are unemployed.

Feeling the effects of stigma has proven to decrease the quality of life of those at the receiving end.

Feeling “less than” because of receiving treatment due to stigma is not the only reason that Kentuckians are not seeking care. There is also a large gap in quality of care throughout different parts of the state.

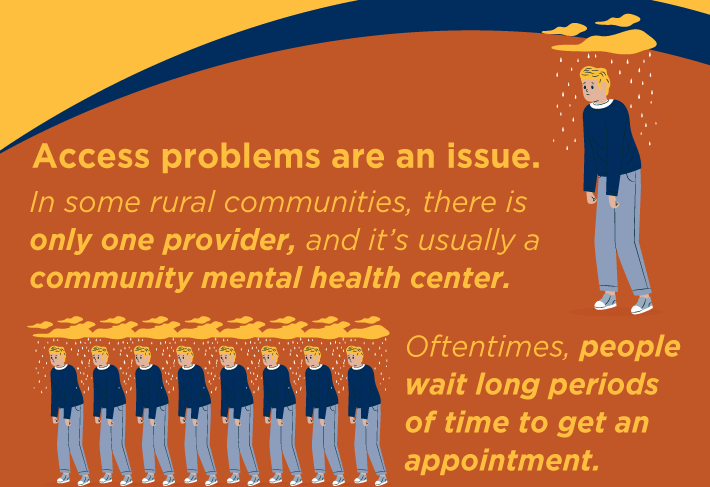

“Access problems are an issue,” Simmons said. “In some rural communities, there is only one provider, and it’s usually a community mental health center. Oftentimes, people wait long periods of time to get an appointment and/or don’t want to be seen there because they will feel embarrassed or think it will embarrass their family or friends.”

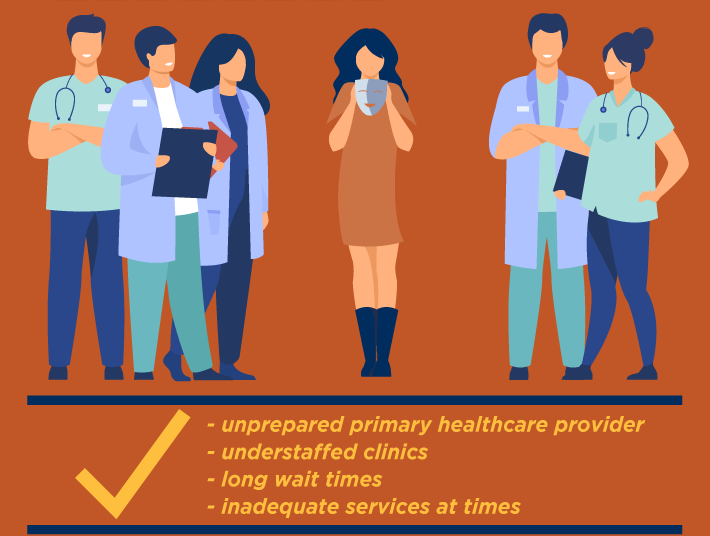

“Other times, in rural communities when people do seek help it’s sometimes through their primary healthcare provider who may be unprepared to manage such illness,” Simmons said. “This can result in negative experiences for patients who will tell you their doctor prescribed something, but it didn’t work. Finally, even when a rural area has a clinic, it’s often understaffed. The staff have large caseloads, and the pay isn’t great, so mental health professionals aren’t drawn to those areas to work. Some student loan forgiveness programs have tried to incentivize working in underserved areas, but there are still extreme shortages of mental health providers which leads to long wait times and inadequate services at times.”

Compounding the lack of available treatment with the lack of financial stability in these rural communities has led to unfortunately higher suicide rates in the state, such as shown by the study of Western Kentucky.

In more rural areas of Kentucky, median income falls more than $11,000 less than the national average. Adding to this, Kentucky’s population is 24 percent rural, compared to the national rate of six percent.

So with Kentuckians not seeking the treatment they need, what exactly are we doing instead? Research specific to Appalachian counties seems to find the answer.

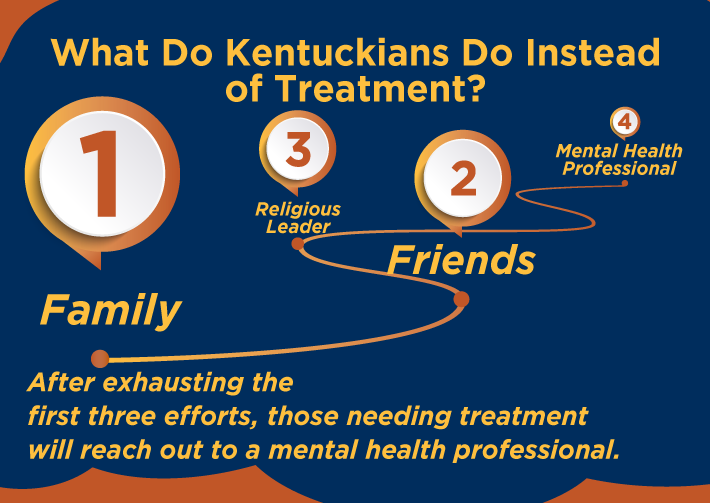

Eastern Kentucky University looked into Kentuckians that were not seeking treatment, and what these citizens were doing instead of getting treated.

Often, according to the research, Appalachian county residents turn to their family and friends when they need to talk about their mental health. If that goes nowhere, they will turn to a religious leader. Finally, after exhausting these efforts, those needing treatment will reach out to a mental health professional.

To improve our lives, and the lives of those we love around us in Kentucky and throughout the United States, it is clear that changes must be made to the idea of mental health. As a country and as a state, too many of us are reaching the point of feeling completely helpless, when there are options available.

“A basic conclusion is that people are still not talking about mental illness,” Simmons said. “Lack of social support (friends and family you can talk to) can lead to worsening depression and in some cases suicide. Social support is something that we consider a protective factor when assessing suicide risk in a patient.”

The social support begins with educating everyone on mental health and adding support to those that have already entered the field.

“Schools need more funding for mental health services and primary care physicians need better training for managing mental illness,” Simmons said. “Businesses and employers need training and education and need to start the conversation in the workplace. Employers need to emphasize that mental health and taking care of yourself mentally is as important as physical health. Additionally, employers should care because it’s costing them dearly not to.”

“Finally, generally speaking, people have to believe they need help and be ready for treatment for it to work,” Simmons said. “That being said, sometimes people need a little nudge. That can sometimes be accomplished by a strong support network. Interventions can be successful if done correctly.”

A way to help nudge people a little bit in these rural communities is to allow for more access to treatment. Simmons explains that by allocating resources and money to these communities to improve their connectivity to the rest of the state and urban areas, you open opportunities for treatment through telehealth and more.

“To move things forward there are many things that can be done with the right funding and resources,” Simmons said. “To begin, more infrastructure for internet services in rural areas is needed. There are still a lot of areas in rural Kentucky where you can’t get internet service even if you can afford it. Once an adequate infrastructure is in place, insurance companies and/or government agencies need to fund things like gas vouchers, internet service, and telephones for people who may need to rely on remote mental health and healthcare services.”

Creating these pathways for treatment will help bring down the rates of untreated mental health disorders in Kentucky, and help those afraid of dealing with stigma from mental health treatment get the help they need, as Julie Cerel, Director of the Suicide Prevention & Exposure Lab (SPEL) at the University of Kentucky and Past-President of the American Association of Suicidology, states.

“Teletherapy means people do not need to leave the house, drive long distances, or get childcare to see a therapist,” Dr. Cerel said. “It means other people do not have to see them entering a mental health clinic. This is a great step to reduce stigma.”

Luckily for Kentuckians, there is already a leader in place ready to take on the surge of telehealth patients from across the state. That leader is SUN Behavioral Health.

SUN Behavioral Kentucky, located in Erlanger, is staffed with an incredible team that is dedicated to delivering compassionate care that puts the well-being of their patients first.

By getting out into the community, SUN Behavioral delivers on its promise to solve the unmet needs of Kentuckians by partnering with local hospitals, doctors, schools, and social service agencies to get out into neighborhoods. By doing this, SUN Behavioral is able to help achieve positive outcomes for those battling mental health disorders along with helping their families, time and time again.

SUN Behavioral has taken it upon themselves to be a leader in the telehealth community, to reach those in underserved communities, and get them treatment that is needed. By providing telehealth services, SUN Behavioral Kentucky is delivering on its promise to create a better future for each and every citizen in The Bluegrass State.

You are not alone. If you or someone you know and love is struggling with depression, anxiety, trauma, or something else, the counselors and professionals at SUN Behavioral are ready and available to hear from you 24 hours a day.

Call today at (859) 429-5188 to begin receiving the compassionate and careful treatment that is needed to navigate the challenges you are facing.